|

I love a parade. There is something about parades that just get to me. I don’t know quite what it is, maybe the collective expression of solidarity towards something, but I will inevitably choke up during a parade. It can be almost any parade- the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade on television, a huge demonstration in favor or against something, a tiny local homecoming parade- it doesn’t matter. There will come a moment where I will just get caught up in the humanity of the moment and that’s it, I’m done. Of course, I have theories about the genesis of this parade love. When I was little, my brother and I weren’t allowed any candy or sugar-sweetened anything. My mom meant well, I’m sure, but our diets were strictly regulated. Parades were this magical experience where people would literally throw candy at you. Once a year, we could just sit on the side of the road as happy people would casually toss my most coveted and forbidden desired treats at us. There was no discrimination or shame to it; if you were sitting there, you got candy. It was delightful. As an adult, no parade has had quite an impact on me as the parade that takes place as part of the events recognizing the struggles, resistance, and thriving within the LGBTQ2S+ communities, known as Pride. I am a cis-het woman in a long-term relationship with a man and really have no place inserting my narrative into this particular discourse, yet the Pride Parade has changed the course of my life more than once. San Francisco Pride, 1996 There is this part of me that can’t help but volunteer. I do not know how I got pulled into doing it, but that year I volunteered for the San Francisco AIDS Walk. My job was to sign people up to receive information about the walk- really, the worst possible job for me. Anyway, together with a small collection of volunteers, we were distributed along Market Street in San Francisco in the hour before the Pride Parade armed with a clipboard and a pile of brochures. We were told to stop pedestrians and ask if they were interested in learning more about the AIDS Walk. If they were, we would hand them the clipboard to get their phone number and address. Easy enough. I hated it, because it meant I had to talk to strangers. I think I collected maybe 10 names. I kind of wandered through the crowd trying to look approachable, hoping someone would think, “That girl might have information about the AIDS Walk. Maybe she has a brochure, or even better, maybe that clipboard that she is carrying is meant for her to collect my name and address.” In other words, I treated that opportunity like I have treated most opportunities in my life- put myself in the right rainstorm and wait for lightning to strike. Once I returned my sad clipboard with the single, incomplete sign-up page, I disappeared back into the crowd and found a spot along the street to wait for the parade. I didn’t have to wait long. I had never been to a parade in San Francisco, let alone a Pride Parade. I had no idea what to expect. If you have ever been to the San Francisco Pride Parade before, you know the sequence of events. First, the police clear the streets. Then there is that tension of waiting, the streets expectantly empty, as if the entire city is holding its breath. In that moment of waiting, the police cars having passed and a near silence in their wake, you hear the roar of motorcycles rumbling in the distance. No- you don’t hear it, you feel it. The feel of those bikes rattles through your body and then the screaming begins as all those people lining the streets begin to thrum with energy, this exuberance growing and growing as you see the bikes coming up the street and hear the wave of people cheering them on as they approach. It’s the Dykes on Bikes, and they are magnificent. That year, the Dykes on Bikes had made their grand entrance and passed by and the crowd was just getting its breath, that first burst of energy almost too much to bear, when a second explosion of energy came careening up Market Street. The noise of the crowd was incredible, only this time it was without the bass of motorcycle engines as accompaniment. This sound was different, it was people cheering a bittersweet song for their everyday heroes, a song for those they had lost and a song for the people who had taken on something bigger than themselves to try to make the world better in their memory. As with the Dykes on Bikes, I heard the crowd long before I saw the group, a wave of noise traveling up Market Street. A group of hundreds of people on bicycles, each wearing a solid colored long-sleeve shirt that collectively created a rainbow. They had decorated their bikes with different photographs and messages, names and dates, remembering people who had died from AIDS. This was the California AIDS Ride 3 group, just back from their ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles, having raised money in support of two AIDS-related organizations. The support from the crowd was unmatched. I watched those people ride by on their bicycles, these looks of wonderment and joy and pride on their faces and I thought, “I want to do that. I want to make a difference.” Santa Fe Pride Parade, 2009 In 2009, the Pride events were relocated from the Plaza to the brand-new Railyard Park. Only opened a year prior, the park was a gorgeous addition to the downtown landscape, but it was still finding its niche within the city’s events. Surrounded by wide, multi-lane roads and few retailors, it would eventually grow into an excellent events space, but it was not a good choice for Pride in 2009, and those big roads were a poor canvas for the still small parade that would begin the weekend events. I love parades. Did I mention that? For the love of a parade, that year I gathered together my two kids, ages 4 and 1, and my older son’s best friend (also 4). My brother also joined us, bringing our 97-year-old grandmother in tow. We found a spot along the parade route where we were about the only people for the whole block, and we parked ourselves on the curb. Grandma had a chair and an umbrella for shade, but the rest of us sat it out old school. We waited for what seemed like forever, sucking on apple sauce bags and eating kid snacks. I recall friends of mine asking if maybe my kids were too young to attend a Pride Parade. I couldn’t imagine why. During the parade, there were people dressed to impress, including some wearing less clothing than maybe they would wear to work. I think maybe this was what those friends were concerned about, but I still am not sure. My friends certainly weren’t worried about exposing my children to political figures driving fancy cars and handing out candy in hope for votes, which is what made up about half of the parade participants. We sat in the sun and cheered and smiled and waved at every group that passed us, excited to be part of this exciting day. The kids got candy, I got my parade, and we had a beautiful day in the sun supporting people in our community- our community being people who live in our city and people who share this same incredible earth with us. What made this notable for me, the reason I’m writing about it now, is meaningful for me more now as a mother looking back at that day 14 years ago. It was important then, but today that day rips my heart out of my chest and stomps it apart. During that parade, as I sat there with my little children and their friend, people in the parade thanked us for being there. People in the parade thanked US. They thanked us for sitting on the side of the road, cheering for them. One young person ran over to me, tears in his eyes, and specifically thanked me for bringing the kids. It took my breath away then, and it does today. What world do we live in that a person would do this, and that people would question my decision to take my kids to cheer for people living their beautiful, courageous lives? Santa Fe Pride Parade, 2023 When I woke up yesterday, I knew it was going to be a hard day. All my joints ached. I had slept poorly that night and struggled to get out of bed. My throat hurt and I was congested and I just felt like crap. The only reason I motivated myself to get up was the promise of a parade. We were going to join the Santa Fe Indigenous Center’s group in the Pride Parade. I didn’t know how I would get through it, but I was going to do it. I wanted to be there to support our Two Spirit relatives, I wanted to be there to support the SFIC and recognize the hard work that everyone at the center is doing. I know how important it is to have warm bodies participating in things like this, and I was more than happy to be able to do this one thing. There aren’t a lot of ways I can volunteer these days, and this was one easy way to participate. I also knew that I wouldn’t be able to participate unless there was room for me in the car they were driving in the parade. Usually the SFIC has a convertible with three passengers and then a group of people walking behind it carrying signs.

Pride events have returned to the Plaza since 2009. The streets in downtown Santa Fe are narrow and perfect for a parade. There are many, many more people attending Pride in 2023 than attended in 2009. The parade was bigger in every way. There were lots of little kids. The roads were full from the start of the parade to the very end. There was joy and excitement. As we moved down the streets, people yelled back and forth, “Happy Pride!” There was so much happiness. The parade route takes you from the state capital down Old Santa Fe Trail to the Plaza. On the way, we passed sculptures by my father and my grandfather. We passed people who were so happy to see us. We weren’t wearing regalia or fancy beads and feathers. We were just ourselves, being Natives, in a parade.  Towards the end of the parade, the route makes a right turn onto San Francisco Street, onto the Plaza. When we turned that corner, the crowd was huge, and the wall of noise was almost too much. That was my moment- the moment I get in every parade where I get lost and cry and feel like I am entirely a part of everything. There were Natives in the crowd lulu-ing for us, we were seen. We were THERE. In that block of people cheering, showering each other with pure love for that single moment, I lost sense of being utterly exhausted and achy and feeling like I was moving through mud, worrying about this whole breast cancer thing and what will happen in the next few weeks, what is going to happen with my job and my husband and my kids and all the other weights on my shoulders. I was there, I was in it. In 2009, I hope our presence on that curb lifted up the people in the parade, the people who looked at us and mouthed the words, “Thank you.” Yesterday, for that little bit of time as we rode along the parade route receiving all that love, I was lifted up. I got my candy, my sugar high. I got to be part of something bigger than myself. Parades make a difference. That’s why I love parades. Even if fleeting, they bring us together, they lift us up, and that makes a difference.

0 Comments

I hate it that those moments in my life that were the most pivotal to my personal development have taken place in the most benign and forgettable places. I never had that special orchestra swelling, clouds breaking event where everything changed, and I realized that I really am the product of all my ancestors’ dreams. I haven’t reached the top of the highest mountain, taken the deep breath of the fresh mountain air and had that epiphany that I had been waiting all that time to have.  Not a pivotal moment. Not a pivotal moment. Not that I haven’t tried. Seriously. I once rode my bike from San Francisco to Los Angeles with my best friend, Lara. We did it to raise money for AIDS-related organizations, and it was a really big deal. It was a pivotal moment in my life in a lot of ways, but in the movie version of someone’s life (not mine), there would be the closing ceremony and the speeches and the music, and I’d lift my bicycle up over my head and realize that I was so much stronger than I ever believed. Instead? I did lift up my bike, but I was so tired, and my knee hurt so much, I was just worried I would hit someone because my bike was wobbling so much. And then I couldn’t find my boyfriend in the crowd, and I really wanted him to see me in my big moment, but he wasn’t there, smiling at me and being so in awe of my amazingness (he wasn’t). That wasn’t an epiphany moment. That was a foreshadowing moment of the breakup 8 months in the future. Instead, I experience my pivotal, life-changing events in the past. They are the conversations I had that never leave me. The words told to me in such a way, I have to return to them because they meant so much more than I realized in the moment. Sitting outside a Starbucks on a breezy spring day. Talking on the phone in my bedroom after being woken from a midday nap. Chatting in a kitchen while my friend kneads bread for dinner rolls. Those little moments when a few words resonated so deeply, my brain captured them in a special chamber so their sound would repeat on a regular schedule to remind me of their lesson, no matter how hard I wanted to forget. Today I was thinking of one of those moments- it was the Starbucks day. I was sitting with my friend, enjoying a coffee and a little break away from campus and I was talking about a possible research project we could do. My friend M worked in a different department on campus, and she and I had been collaborating on grants. I respected her deeply- she had a strong commitment to serving her community and was always reminding me of the importance of our accountability to community and maintaining our Indigenous values in our work. Her clarity was inspiring, and more than a little intimidating. No matter what ideas I pitched, she would always return with, “has the community asked you to do this? If the idea doesn’t come from the community, it’s not a good idea.” There we were, the sun was warm on my face, the wind was blowing my hair into my mouth, eyes, lips. Talking about research with M could be frustrating because she would remind me every time about the responsibility we had to our communities. I was trying to get tenure, and the tenure clock doesn’t care about community. The conversation was a little tense already, and then I said something that included the phrase, “target population.”

“I don’t care what you say. I am not anyone’s target, and we aren’t a target population.” This is when I started to backpedal. This is when she got even more angry. This is when I got angry that she wouldn’t even try to see it my way. We were fighting outside that Starbucks on that breezy spring day. Then I was embarrassed, and that led to me being defensive. I was the kind of angry where tears fill your eyes. But I was also stubborn, and I didn’t want to appear weak before M, this person I respected so much. We somehow wrapped up our conversation- I don’t know how, I just remember leaving feeling like I was going to vomit. And then that pivotal moment was captured in the sound chamber of my brain, echoing whenever I hear the term “target population.” It’s been a decade, and that sound is still there. To be present when someone experiences being called one of these terms is so painful, especially when they are unafraid of demonstrating their pain and anger- it is awful. I am ashamed I was so thoughtless, so persistent when my friend responded so honestly, and I was such an ass with my backpedaling and pedantic explaining. The damage that research causes, even with these little phrases, it hurts. It hurts people on a personal and visceral level. There is nothing abstract about being called a target. This language dehumanizes people to such a degree that it makes them actual points to be focused and shot upon. To dare talk about people who are survivors of centuries of genocide using this language is beyond insulting. The language of research is damaging. Looking back, I am grateful that M didn't hold back. She told me, in no uncertain terms, that the language I was using, the attitude I was taking, all of it- I was wrong. She showed me what so many people swallow up, and I am so very, very sorry that I made her feel that way. Ultimately, M and I were able to find a resolution. I don’t know how, I don’t remember. I do know that I never used that language again, and we emerged from that time better friends, even with that pain behind us. M has taught me so much over the years, but this lesson was the hardest. Those words that I used, that she responded to, became a life lesson that far surpassed riding my bike 500+ miles, or moving across the country to go to grad school, or making the leap of faith to get a PhD. Learning to really listen- that is my epiphany moment. As hard as I have tried to forget.

I had tenure once. At an R1 university. I left that job because of a lot of reasons too complicated to go into in a single blog post. When I am talking to people about my decision to leave academia, they often ask me if I'm glad I made the decision to leave. Hell yes. I shouldn't be too honest here, because who knows, I might actually want to work at a university again some day. Not today, but maybe someday. Anyway, people usually ask me what I miss about academia. Not much, I say. "But don't you miss the..." they ask. "Nope." I say. I sacrificed too much to miss anything. It's hard to explain. If I want to be entirely truthful, I do miss one thing. I miss working with PhD students. I don't miss sitting across the desk from students and trying to convince them to drop out because their lives were falling apart and they were failing their classes and going broke trying to work full time and take all their classes in two years and raise their families and be the primary wage earners and understand this really complex stuff that we were teaching that was NOTHING like what they had learned as masters students. That was heartbreaking.  brainses by Stephanie Curry on Pixabay brainses by Stephanie Curry on Pixabay I miss having students come to me because they had these amazing puzzles in their brainses and they needed help figuring out how to assemble those puzzles. Often those puzzles were a combination of theory, methodology, feasibility, and basic time management. I loved those puzzles. It was so much fun when a student came to my office and they looked so frantic, on the edge of a panic attack, unsure how the hell they were going to answer that research question that they had been working out for the past few years, and how they would do it before they ran out of funding/time/energy. It makes me excited just remembering. I am a lot like those students. I procrastinate with the best of them. I have read just about every single productivity book. I have gone through so many different productivity systems, trying to figure out how to maximize my time with the least amount of effort. When I was writing my dissertation, I spent more time thinking about how to find time to write the dissertation than I actually wrote. Since then, I've learned a lot about working well, how I work, and how to help other people work. I like to think that I've actually gotten pretty good at helping people get past those obstacles in their paths, helping them realize that the boulders are really just little stones they can easily navigate past. It takes practice, but there are tools you can use to get through, even if you have a nonlinear brain like mine. How to Do That Thing So you have a thing you need to do. It's huge, it has a lot of parts, and the longer you wait to start, the scarier it gets. Are you getting so freaked out by the thing, you are considering moving to another country? Have you thought about changing your name and address? Are you wondering why anyone ever thought YOU would ever be able to do that thing, you are in so deep if you back out now everyone will think you are stupid, if you back out now you're just proving to everyone that you really are stupid and insufficient and a disgrace to your family name? Yup. Been there. Before we start, let me reassure you that I have been there. I may be there right now, in fact. I may have been up half the night having those very thoughts. You are not alone. I want you to know that you ARE the right person for this, and you were selected to do it because you are the ONLY person who can do it. It may not feel like it right now, but it's true. Let all that stuff go. It's just the monsters whispering in your ears, and we will just leave them in the past. They do not belong in your brain any more. If they come back, just tell them that Dr. Haozous said that they don't belong in your brain, now they can kindly go away. If they don't leave, then you can go take a shower or something, wash those nasties away. Okay, now that we've put the monster nasties in the past, I want you to get out a blank sheet of paper and a pencil with a good eraser. I know, everyone wants to use paper from the recycled pile, but for this I really want you to use something clean and pristine. I know everyone tells you to make lists, and we nonlinear people hate that, so I'm not going to start with lists, but you know where this is going. TIPS (in list form)

**This blog post was inspired by a facebook question from a friend. Thanks, Geri!

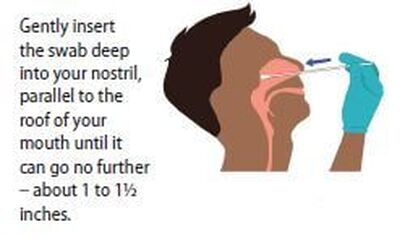

I know. I KNOW! It's been a minute. Long story short, there was a virus. It found me. It decided that my body was deeeeelicious and ideal and a good place to retire. And so it did. The end. Longer version: In March of 2020, we went on a dream vacation to New York City. This was when the newspapers were saying things like, "isolated cases" and "not a big concern," and "flu-like symptoms, but most have no symptoms." Hey, guess what? They were wrong. It wasn't isolated. There was a lot to be concerned about. It shouldn't come as a surprise that I got sick.  cdc.gov cdc.gov This was back when testing was limited, nobody knew what to expect, there was no PPE, and the world was loosing its collective mind over stuff like toilet paper. Remember that? A lot of people look back fondly on those days and think, ah, sourdough starter. Not me. I look back and think, AH! Explosive diarrhea! AH! Can't breathe! AH! The ER Doctor won't even examine me because she is an asshole and the COVID testing has high false negative rates but she doesn't want to get within 6 feet of me and even though I get dizzy talking she won't even listen to my lungs unless I beg her and then she barely puts the stethoscope on my body and even then she only puts it on my shirt, not on skin, so no wonder she can't hear the pneumonia in there and thank god I can take care of myself and thank god I don't get sicker and thank god I know a little something about how to care for yourself and not to panic and thank god I am still alive today. Never in my wildest days would I think I would be grateful to be able to breathe without pain. Yet, here I am. It is now August, 2021, as I write this. A year and 5 months since I was sick. Six months? I hate calendar math. Five months. Anyway, it's been a long time. I'm still sick. It took me about 6 weeks to recover to the point that it didn't hurt to breathe. 2 months and I could walk to the corner and back. By May, I was trying to run and rebuild my health. And then the weird symptoms started. A strange rash on one leg (livedo-reticularis-like lesions). constant allergies. raging dry mouth and oral candidiasis. There have been many more, but the worst and most constant COVID companion has been exercise intolerance. I am the same person, but I can't DO anything. I have to sleep all the time. Or rest. I spend all the time I have laying on the couch listening to audiobooks. It's a drag drag drag. Anyway, I'm still here. I'm still working, writing, researching. But instead of doing all the fun things that I used to do, my life is much more contained. I've learned about pacing. I have no spoons. Well, I have limited spoons. I'm still trying to figure out just how many spoons I have. It's not many.

|

AuthorI'm a Chiricahua Fort Sill Apache Nurse Researcher. I write, speak, and think about health equity and parenting in our complicated world. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

Views expressed here are my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer.

© 2023 all rights reserved, DrEmilyHaozous.com | The content in this blog is the exclusive property of the author unless otherwise indicated. You do not have permission to take content from this blog and use it on yours. You may use short excerpts and you may link to this blog, it is expected that any content has full and clear credit to the source content.

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed